The C919: A Masterclass in Technology Transfer, and China's Newest Pacing Threat

The origins of China's burgeoning commercial aviation dominance and its implications for the future of global air travel

Two headlines that are interesting on their own but even more interesting when explored in combination are the recent quality and production issues at Boeing, together with the increasing global viability of Chinese state-owned commercial aviation firm COMAC’s C919 and its other models. It feels convenient that the C919 debuted internationally at the Singapore Airshow only months before quality failures at Boeing became round-the-clock reporting for business media outlets everywhere, but given the nature of the airline industry, experts feel certain that any competition the C919 may introduce to the Boeing-Airbus duopoly is likely years away from materiality.

Although such predictions are likely true, the Chinese government has indeed been planning the development of an ‘indigenous’ commercial aviation industry for decades now, and it has a blueprint for future dominance in commercial aviation that has been deployed in other mass transportation sectors to appreciable success. Hence, it is imperative that western firms understand the likely trajectory of commercial aviation in China going forward, as the most existential threat to western commercial aviation predominance now emanates from China.

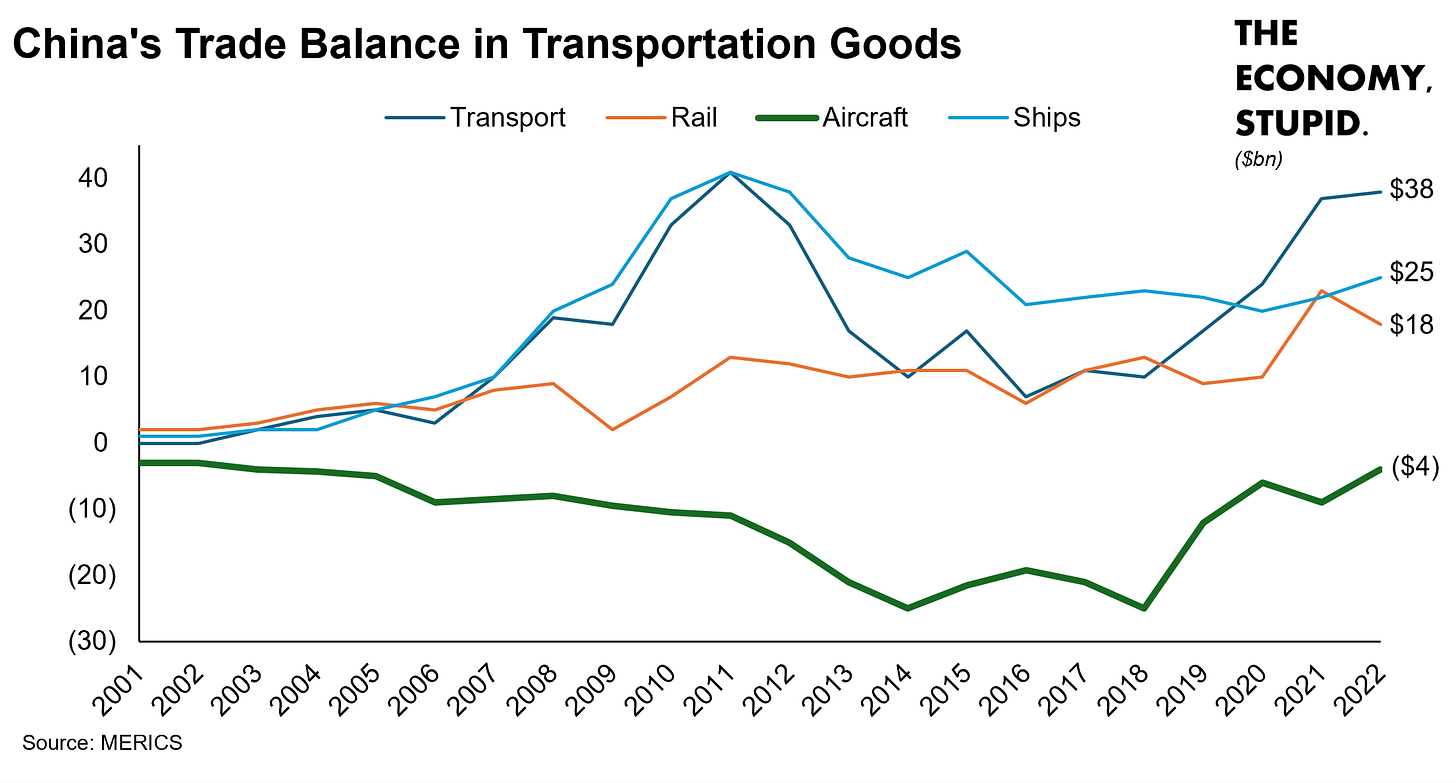

China is undoubtedly a ‘transportation superpower’, touting multi-billion dollar trade surpluses in every transportation sector (Figure 1) except one: aviation. This is not a coincidence; as researchers at MERICS indicate, “the ‘transportation superpower’ concept (交通强国 jiāotōng qiángguó) first emerged in 2016 and appeared over 700 times in key policy documents by September 2023,” depicting the preoccupation with which the Chinese central government embraced transportation investment during the period. That aviation is the last remaining frontier for Chinese transportation dominance is no surprise, either. As United Nations University researchers explain, “aerospace manufacturing is a leader in technology intensity and is also highly capital intensive. New entrants face a steep learning curve. Access to technology for latecomers is limited by the very high entry costs [and the] industry is characterized by imperfect competition, non-homogenous products and major economies of scale. Fixed initial development costs are extremely high. To overcome private underinvestment in new technology, governments support manufacturers, either through launch subsidies, export subsidies, military procurement or market protection.” The nature of the aviation industry envisioned by the researchers is a treacherous one in which new entrants stand no chance at success unless backed by benevolent government development programs. Additionally, the researchers go on to highlight particular challenges for ‘latecomer’ firms, stating that “[the] aerospace industry presents latecomers with a special challenge because of its technologically complex products ... A cheaper but less reliable or less advanced consumer electronics product can be sold in large numbers if the cost is low enough. This trade-off does not exist for aerospace products. Quality standards for firms entering the market, even at the lower end, are higher than in any other sector, given that an aircraft or spacecraft is as reliable as its weakest component. Latecomer firms cannot sell their products unless they successfully meet the high standards set by the global industry leaders.”

Critics of the C919 and COMAC’s other models often point to the large number of western manufacturers (Figure 2) involved in the models’ supply chains as a comment on COMAC’s lack of originality and heavy reliance on western manufacturing, but with the understanding of the industry provided by the United Nations University researchers’ report, these critiques feel irrelevant; all internationally-recognized commercial aircraft are products of highly globalized supply chains, and the high degree of regulatory scrutiny on commercial aircraft quality inherently necessitates a certain level of uniformity in the ‘look and feel’ of commercial aircraft. Furthermore, many of the similarities between western and Chinese commercial aircraft are a direct result of a western desire for involvement in the burgeoning Chinese commercial aviation industry in the late 20th century, so with additional historical context, such critiques feel even more misplaced.

Western firms have played an important role in the development of Chinese commercial aviation since the industry’s very beginnings. The first collaborations between Chinese and western aviation firms began in the mid-to-late eighties and nineties, with a 1985 coproduction agreement between McDonell-Douglas (acquired by Boeing in a $14 billion landmark acquisition in 1997) and a Chinese state-owned firm, which took ten years of negotiations closely followed by the US Department of Commerce to finalize, highlighting the industry’s complexity as well as its governmental significance. Interestingly, even from these earliest encounters between Chinese and western firms, the technology transfer process seems to have been taking place. The United Nations University report highlights many similarities between the ARJ-21, COMAC’s first commercially viable aircraft, and the McDonnell Douglas planes that were assembled in Shanghai. The report goes on to state that, “[coordinated] by a government-led commercial aircraft company [(a COMAC predecessor)], the four plants involved [in the development of the ARJ-21] (Shanghai, Xian, Chengdu and Shenyang) were the same as the ones in the [McDonnell-Douglas aircraft] project”. According to RAND, the first true commercial aviation joint venture between western and Chinese firms took place in 1996, when Pratt & Whitney and Chengdu Engine Group established an aircraft engine production facility. Since then, joint ventures have expanded drastically, with nearly every major firm in the commercial aviation supply chain having a presence in China, though the equity positions of foreign firms in such JVs are often minority or non-controlling.

Although minority equity positions in joint ventures as well as the broader environment of intellectual property (IP) espionage in China put western firms at risk of nonconsensual technology transfer, many western firms were aware of such risks even in the 20th century. RAND-conducted interviews with western aviation firms doing business in China showed that “all [interviewed western aviation firms] were aware of the challenges of protecting technologies from Chinese competitors,” but the report still cited “[providing] support to Chinese customers, [benefitting] from a competitive source of parts, [generating] sales to Chinese airlines, [purchasing] Chinese components as a marketing tool to encourage Chinese purchases of aircraft, [participating] in the C919 program, [and enhancing] the company’s image in China,” as reasons why engaging in the Chinese commercial aviation industry justified the risks for interviewed western firms. Even in western aviation firms’ reasoning for entering China there were clear contradictions; although increased access to China for western aviation firms meant greater sales opportunities and a bigger total addressable market, their willingness to participate in the growing Chinese commercial aviation industry facilitated its development to the point of harboring real, existential competition to the status quo that has largely buoyed both Boeing and Airbus for decades. In hindsight, although western aviation firms understood the risks of doing business in China, it seems that their IP safeguards and other strategies for ensuring predominance as collaboration with Chinese firms increased largely failed.

This is not necessarily a surprise, as the Chinese central government and state-owned firms had the benefit of experience in developing other indigenous transportation industries, whereas western aviation firms, being the progenitors of the commercial aviation industry, were facing an emergent threat in state-backed latecomer COMAC. The Chinese central apparatus took its learnings from working with foreign firms in the high-speed rail and shipbuilding industries, for example, and applied them to the aviation industry to similar effect. In the MERICS report cited earlier, researchers outline a 5-step path of industry development that the Chinese government seems to have used in the high-speed rail and shipbuilding industries and reused in the aviation industry:

“

1. Create market demand through state support

2. Build up domestic industry with the aid of foreign companies

3. Strengthen innovation system to develop indigenous technology

4. Crowd out foreign companies in China

5. Push into global markets

”

Given the continued flight success of the ARJ-21, the recent commercial introduction of the C919, and the ongoing development of the C929, the Chinese aviation industry now seems to be somewhere between steps 3 and 4; now that the development stage is largely complete, more time is needed to understand how Chinese aviation industry planning will play out commercially in competition against the likes of Boeing, Airbus, and Embraer, but given the compelling strategy laid out by MERICS, one can predict in broad strokes what may be coming.

As it stands now, the Boeing-Airbus duopoly is largely safe, but a ‘ceteris paribus’ assumption in the commercial aviation industry, especially in light of recent challenges (of varying kind) at both Airbus and Boeing, is not a prudent one. Although both Boeing and Airbus have yearslong orderbooks and fleets of commercially proven aircraft (both things COMAC does not have), quality issues at Boeing realistically call much of its orderbook into question. Boeing’s lagging reputation has broadened the gap between it and Airbus, with 2023 being the “fifth consecutive year that Airbus has delivered more planes than Boeing,” but the burden of being the only large-quantity aircraft supplier of repute has put immense strain on Airbus, as evinced by “a cautious note on its financial objectives as supply-chain woes persist and rival Boeing Co. remains mired in crisis,” during its 2023 fourth quarter earnings call. Going into the back half of the decade, if Boeing continues to falter and Airbus continues picking up its rival’s slack to its own detriment, the western commercial aviation industry will have to reckon more substantively with the likelihood of a Chinese entrance into the global commercial aviation market.

Regardless of what happens globally, COMAC will almost certainly begin taking Chinese market share from Boeing, Airbus, and others given the Chinese transportation industry development playbook and the high levels of government support COMAC has already received to this point; the Chinese central government will not allow one of the most recognizable manifestations of its industrial policy to fail, and certainly not at home. Winning in China often portends success elsewhere though, given the sheer size of the market. In its 2024 commercial market outlook, Boeing predicts new aircraft deliveries to China will amount to 8,560 new planes over the next 20 years, or about a fifth of the world’s entire new aircraft deliveries during the forecast period. If COMAC can leverage its state-owned status in the Chinese domestic market, it can develop a foothold that enables advantageous, internationally applicable economies of scale, just as Chinese car manufacturer BYD has done with its sales of electric vehicles.

Although most western aviation industry practitioners believe the C919 and other COMAC planes will eventually be more significant global players, the urgency with which different firms are strategizing for this likelihood differs. Amongst aircraft lessors, Air Lease CEO Steven Udvar-Házy says that, though “[the] CCP and COMAC are very interested in selling the C919 … it’s a one-way dating relationship,” indicating his bearish sentiment for the C919’s near-term potential. This is in stark contrast to AerCap’s apparent embrace of the C919, having been one of the first non-Chinese firms to order the aircraft in 2023. Amongst aircraft manufacturers themselves, Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury “[predicts] that the C919 will be a competitor for the Airbus A320neo towards the end of the decade,” while “Boeing’s Asia-Pacific commercial marketing managing director Dave Schulte said the U.S. plane maker is factoring in competition from the C919 in its long-term forecasts”.

Although Chinese commercial aviation predominance is still a ways off, the groundwork for real commercial aviation competition with the west has been laid: China has proven its ability to produce narrowbody (and soon widebody) aircraft at commercial scale. What follows is a yearslong period of live flights (mostly in China by Chinese airlines) and rounds of approval from international regulatory bodies, after which a global introduction of COMAC planes is more likely. The hard part (establishing an indigenous commercial aviation supply chain) though, is largely already done, and is a testament to robust Chinese industrial policy during reform and opening-up and thereafter. As the ARJ-21 and C919 develop a more substantial domestic presence in the years to come, and as the C929 nears completion, the western firms at the vanguard of the commercial aviation industry will inevitably experience new, formidable competitive pressure from COMAC and China’s broader aviation sector, which these same western firms (and their predecessors) had a hand in developing just decades ago.

Mentions: BA 0.00%↑ ABUS 0.00%↑ AER 0.00%↑ AL 0.00%↑ ERJ 0.00%↑

Be sure to subscribe here and connect with me on LinkedIn.

Can you comment on the Chinese development of commercial jet engines and avionics?