'Mercantilism' vs. Moving up the Value Chain, Part I:

An extension of Pascale Massot’s ‘Vulnerability Paradox’ through a comparative analysis of Chinese involvement in the Congolese Cobalt and Indonesian Nickel industries

This essay was originally published in the “China in the Global South” Special Issue of the Tsinghua International Relations Review.

Since the early 2000s, China’s unprecedented demand for commodities has led to its rise as dominant consumer in several global commodity markets. For example, China became the world’s number one importer of potash in 2002, iron ore in 2003, copper in 2008, and uranium in 2010; in just a few decades after its period of reform and opening-up, China had arrived as a node of real significance in the world’s commodity supply chains. China’s rise as dominant global commodities consumer displaced incumbent dominant consumers (often Japan) and brought about substantive changes to the structure of many individual global commodity markets. Although it seems intuitive that such changes would always have been positive for China and at its behest, the opposite was often just as likely; even though China’s demand for commodities granted it a significant role in numerous commodity supply chains, the country was not always able to leverage its newfound significance into positions of market advantage. Paradoxically, in some cases China was even unable to leverage its dominant consumption to prevent unwanted changes in market structure as a result of its rise and displacement of other consumers. Understanding this paradox of market power and vulnerability lies at the crux of China’s Vulnerability Paradox, Pascale Massot’s recently released examination of Chinese market power through case studies of its impacts on the global markets for iron ore, potash, copper, and uranium. In the book, Massot puts forward a novel and compelling framework for understanding why China’s rise as dominant global commodities consumer yielded different outcomes in different individual commodity markets. Her framework examines how concentration asymmetries between commodity producers and consumers impact the balance of market power between the two groups, and how this balance of power influences changes in market structure. Although Massot is primarily concerned with ‘the capacity and quality of the coordination that takes place among global producers and Chinese stakeholders … at the import/export interface,’ employing her ideas in the examination of Chinese interactions with specific commodity-producing countries yields compelling insights about the impact China’s rise as dominant global commodities consumer has had on the economic development of various countries in the global south.

Although China’s investments in the extraction of natural resources across the global south have often been characterized as exploitatively ‘mercantilist’ or ‘neo-mercantilist,’ an analysis of specific China-global south interactions in specific commodity markets reveals a more nuanced narrative. By applying Massot’s ideas to case studies of Chinese involvement in the Congolese cobalt and Indonesian nickel industries, Chinese market power in both cases will be clarified and its implications and outcomes in both countries will be better understood.

The Contours of the Congolese and Global Cobalt Trade

As the world’s shift towards renewable energy has accelerated, cobalt has been recognized as a critical mineral for the transition due to its usage in battery manufacturing; battery demand accounted for 73% of the cobalt market in 2023, and 93% of total demand growth in the same period. An overwhelming majority of the world’s mined cobalt comes from one place: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (Figure 1). In 2023, the second largest source of cobalt production following the DRC’s 182 kilotons (kt) was Indonesia with a mere 16 kt (though Indonesia is investing heavily in greater cobalt mining capacity). As nearly 80% of the world’s cobalt is sourced from the DRC, the country is a critical point of concentration in the global cobalt supply chain, but at the domestic level, cobalt production in the DRC is relatively fragmented.

Extraction of Congolese cobalt is divided between large scale miners (LSM) and artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM), with ASM output historically providing approximately 10% of total Congolese cobalt production and trending higher during strong pricing periods (the global cobalt market is currently in a supply glut that has driven prices to recent lows). All legitimate ASM and LSM mining operations in the DRC are licensed and overseen by Gecamines, the Congolese state mining company. Gecamines also often invests as a minority stakeholder in joint mining ventures with foreign LSMs and arranges “off-take” agreements for trading rights to a specific proportion of a mine’s total output which, in addition to tax revenues from LSMs, helps the Congolese government benefit directly from granting LSMs concessions to Congolese mines.

Within the LSM segment, a number of large multinational miners including Swiss trading giant Glencore, China Molybdenum (CMOC), and Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) are active in the DRC, though Chinese LSMs make up the lion’s share of Congolese mining capacity with stakes in 15 out of 19 cobalt-producing mines as of 2020. Despite their formidable and growing presence in the DRC, Chinese cobalt miners seem to only partially coordinate their operations if at all, and LSMs of other nationalities remain competitive. Chinese influence over cobalt mine production (7% cobalt content) and cobalt intermediate production (22%-27% cobalt content) has been estimated at 14% and 33% respectively as late as 2016, indicating significant Chinese influence in the cobalt supply chain but not complete dominance or control. Additionally, the two most productive Congolese cobalt mines (which together produced 97 kt of the DRC’s 182 kt of 2023 cobalt production) are controlled by CMOC and Glencore respectively, further contributing to fragmentation (based on country of origin) among producers.

The largest consumers of raw and intermediate cobalt are global cobalt refineries, of which China again controls the lion’s share, with more than 78% of 2023 global cobalt refining capacity estimated to reside within the country. Like Chinese LSMs operating largely independently of each other in the DRC, it seems there is very little cooperation between domestic Chinese refineries in their interactions with global stakeholders, contributing to fragmented demand by Chinese refiners despite the country’s dominant consumption position. 11 unique Chinese cobalt refiners were identified in a 2016 report when China controlled 50% of global refinery production, but as the country’s dominance of refining capacity has grown, the number of unique Chinese refiners seems to have grown as well; in recent supply chain due diligence reports from multinational manufacturers like Renault, Ricoh, Asus, and Stellantis, upwards of 22 unique Chinese cobalt refiners are identified.

Despite the country’s outsized and growing share of cobalt refining capacity, the proliferation of unique Chinese refiners frustrates attempts at leveraging this dominant consumption into a position of concentrated, substantive market power. Together with the just-as-fragmented supply side, it is evident that China’s unprecedented hunger for cobalt has not translated into a clear position of market control in the extraction of Congolese cobalt or in the broader global market for the mineral; as Chinese production of cobalt ore and intermediates as well as Chinese cobalt refining capacity are divided across numerous stakeholders acting largely independent of one another, the country’s ability to wield market power through central organization and coordination is diluted.

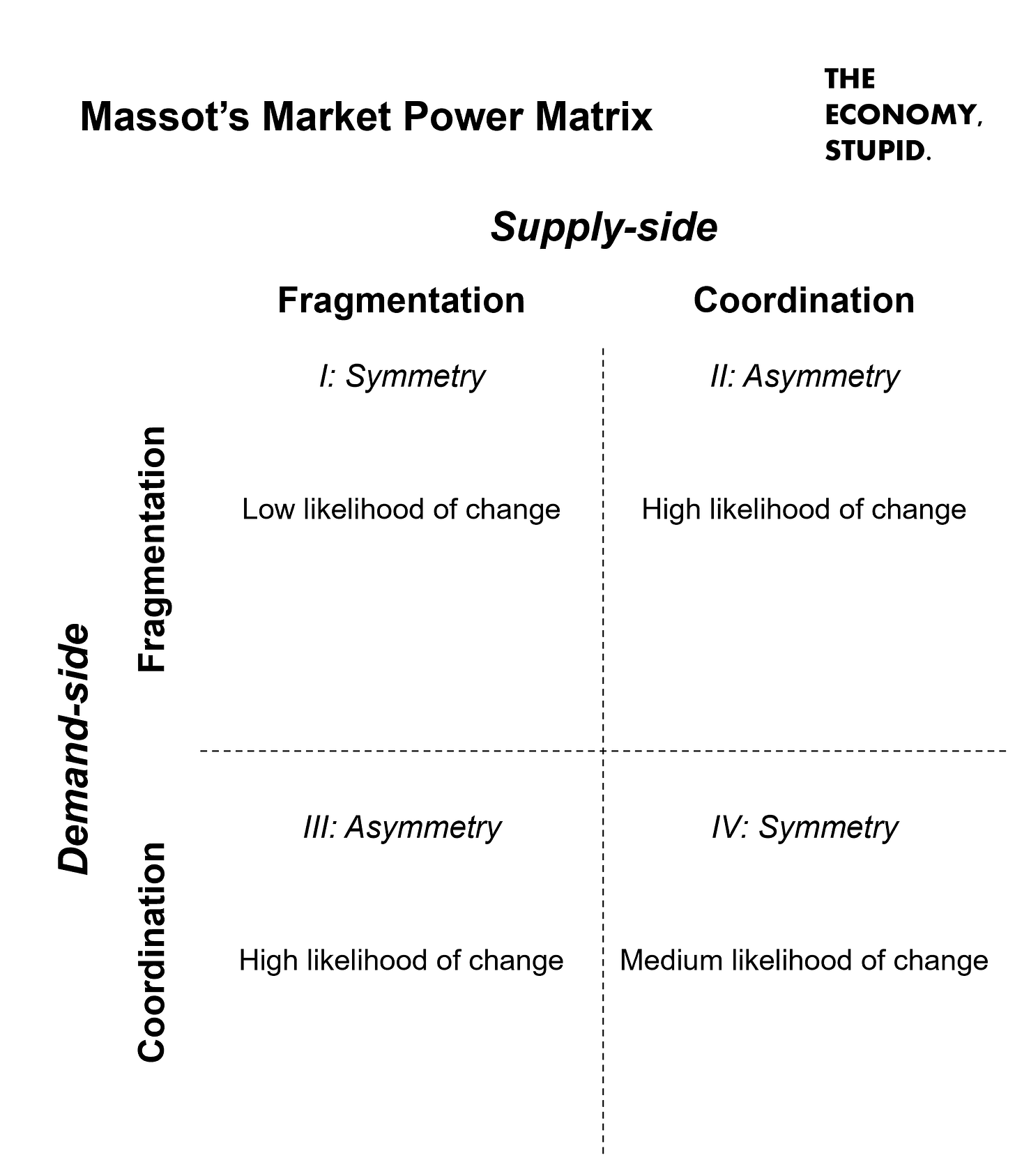

Coordination capacity, described by Massot as ‘the capacity of various … market stakeholders to overcome collective action problems and work together effectively,’ is central to her conception of market power because ‘coordination facilitates cohesion, the pursuit of certain procurement goals, and also increases bargaining power.’ A foundational tenet of Massot’s framework is her claim that there exists a ‘causal relationship between … the relative capacity of consumers [or] producers to coordinate behavior [and their ability to affect] market institutional change at the global level.’ From this understanding of coordination and its influences on market power, Massot introduces a two-by-two matrix that plots the relative coordination or fragmentation of consumers in a given market against that of the market’s producers (Figure 2). When a market’s consumers and producers both operate in fragmented capacities, as is the case with Congolese cobalt, Massot claims that this symmetry will ‘likely … lead to competitive dynamics,’ which in cobalt are borne out in recent record supply gluts and pricing pressure. Despite their dominant market share in both the extraction of Congolese cobalt and global refining capacity, the relative fragmentation of Chinese cobalt producers and consumers (both domestically from a refining perspective and globally from an extraction perspective) largely negates claims of institutional control of Chinese stakeholders over the Congolese or global cobalt industry (Figure 3); if Chinese cobalt extraction and refining practices are in fact mercantilist, such practices are not exclusive solely to LSMs and refiners of Chinese origin.

Be sure to subscribe here and connect with me on LinkedIn.