Home Depot All-in on Pros, Half Measures for DIYers at Lowe’s:

How differing views on the housing market are driving differing strategies at America's leading home improvement retailers

If you live in the United States and have ever had to paint a bedroom or put up a shed, chances are you visited one of two stores (or often both!) at some point during the project timeline: The Home Depot, or Lowe’s. The American imaginary is filled with famous consumer retail ‘rivals’ or ‘duopolies’: Pepsi / Coke, KFC / Popeyes, and Windows / Mac, to name a few. In each of the three aforementioned cases, you probably have a (firmly) definitive favorite, but do you really have a favorite hardware store?

I have always found myself viscerally attracted to The Home Depot’s almost neon, construction-sign orange for reasons I don’t fully understand (especially since orange is apparently “universally disliked”), but other than that, there is no clear favorite in my mind and seemingly the minds of many other American consumers. Even on more tangible metrics of business, these firms feel almost neck and neck.

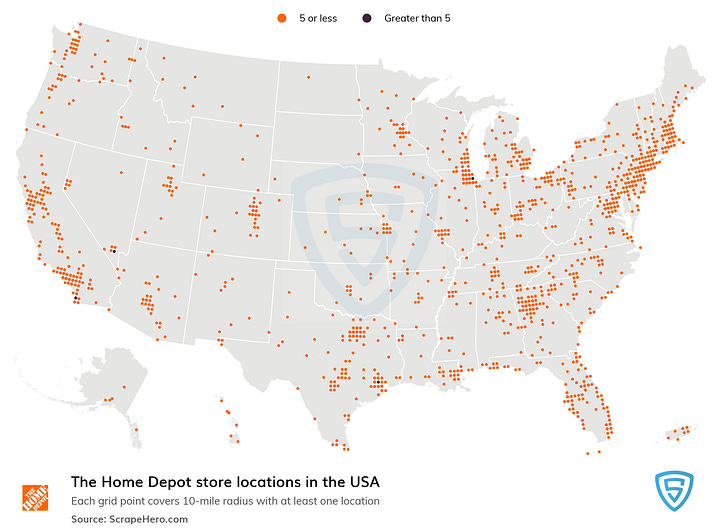

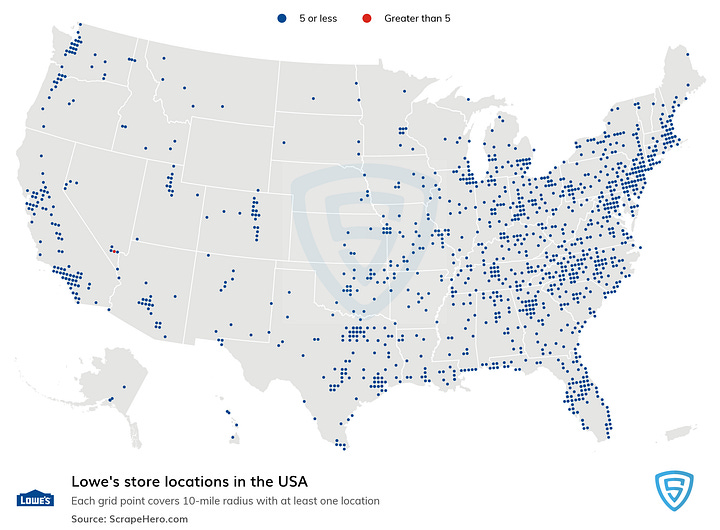

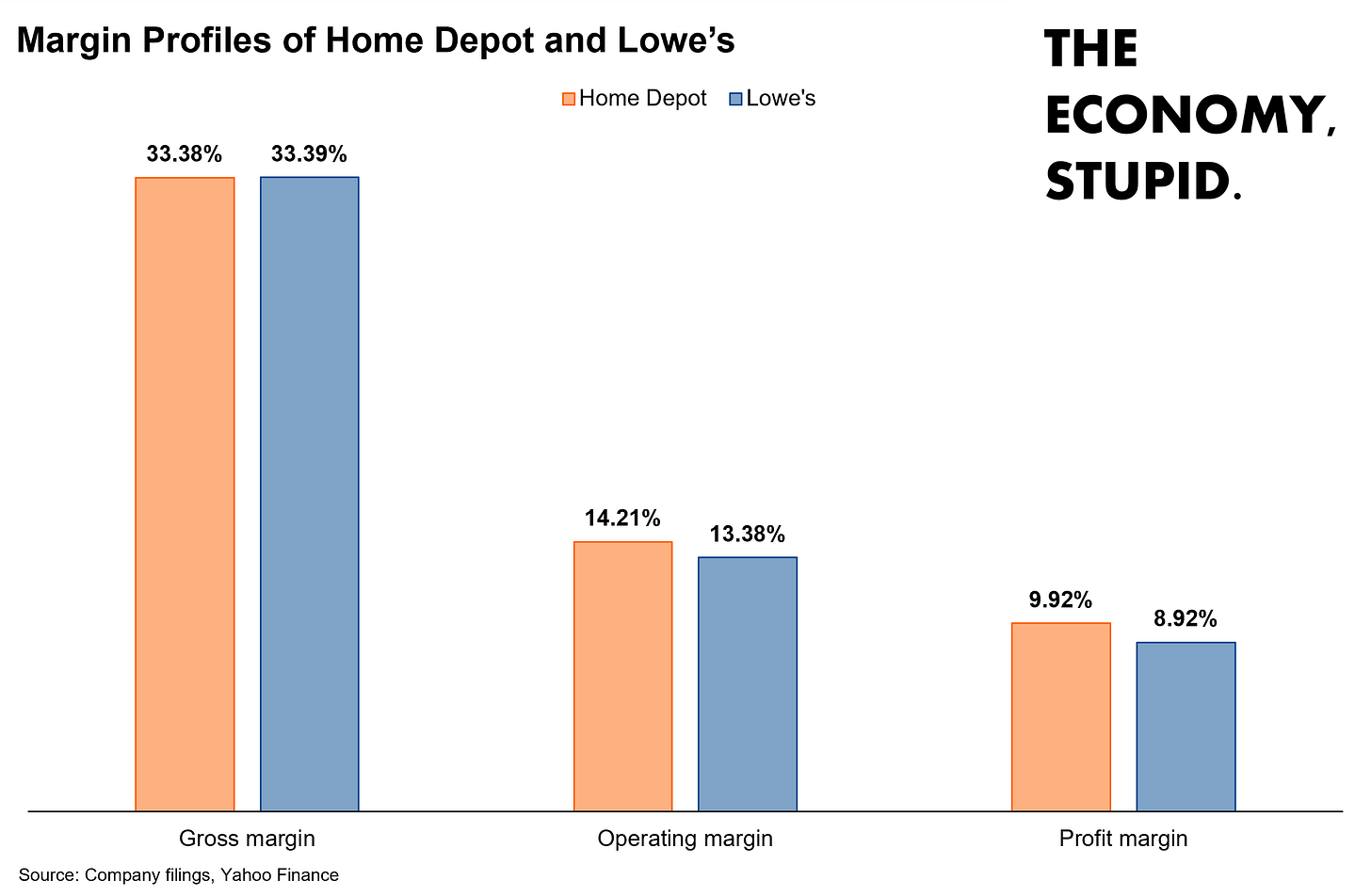

Geographically, both Lowe’s and Home Depot blanket large swaths of the United States, though Home Depot has about ~13% more physical locations than Lowe’s (Figure 1). At the single store level, the firms also go for very similar layouts. Note the inclusion of outdoor garden centers, checkout placements, and similar department labels across both maps in Figure 2.

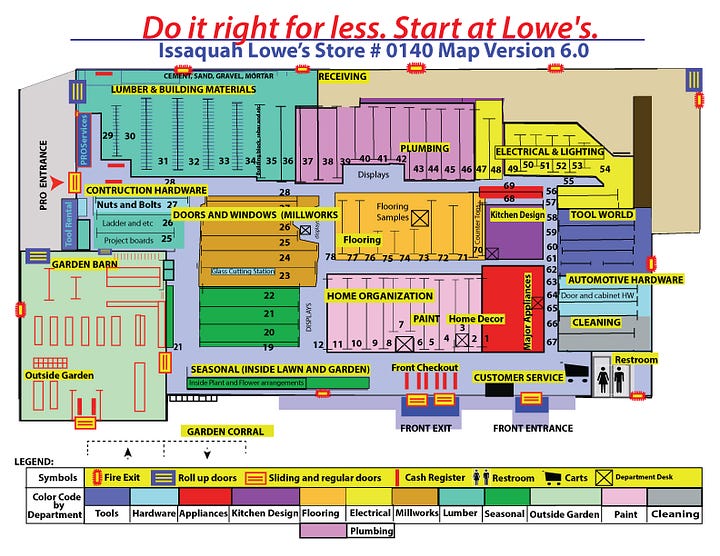

From a margins perspective, the companies are also strikingly similar, as Figure 3 shows. The largely identical margin metrics are in line with the two companies’ near-identical stock performance over the last year as well.

Although similarities between the two companies abound, recent deals suggest that their focuses might be diverging.

The Home Depot has pursued an impressive string of post-pandemic deals meant to differentiate itself as the dominant seller to professional customers (“Pros”), with its latest acquisition being SRS Distribution, a specialty distributor of roofing material and other building supplies. Meanwhile, a recently announced strategic partnership with DoorDash makes Lowe’s products available for same-day delivery on the app historically associated solely with food delivery, an interesting ploy to “reach new [do-it-yourself (DIY)] customers,” as one Lowe’s VP puts it. Given historically poor Pro sales penetration at Lowe’s (the current DIY / Pro sales mixes at The Home Depot and Lowe’s have been ballparked at 50% / 50% and 75% / 25%, respectively), its strategy is less of a single focus on DIYers and more on “[enhancing] … omnichannel capabilities [to] position Lowe’s as a one-stop shop for DIY and Pro customers to get everything they need across all of their projects,” whereas The Home Depot’s acquisition strategy is focused on “[enabling] the company to better serve complex project purchase occasions … while also establishing The Home Depot as a leading specialty trade distributor across multiple verticals.”

Through its acquisitions, The Home Depot is effectively expanding out of providing tools and materials for pure home improvement and increasingly venturing into the provision of tools and materials for home building and more complex, multi-stage contractor-led projects. Through its partnerships with DoorDash and others as well as its investments in new technology and rewards and loyalty programs, Lowe’s is reinventing itself as a true home improvement ‘big box category killer,’ with a range of tools, materials, appliances, and branded merchandise meant to conveniently and affordably satisfy the broad demands of DIYers and smaller ‘semi-’Pros that don’t need the more specialized range of materials The Home Depot plans to offer through its newly-acquired portfolio of brands (SRS Distribution, Construction Resources, and HD Supply). Both companies are betting long on American housing and homeowners but in rather different ways. Whose strategy is “better”? Whose will ultimately prevail, and why?

Going forward, it feels like comparing these companies in such an apples-to-apples way might be flawed, as The Home Depot becomes increasingly specialty-oriented, and Lowe’s continues to execute on its more consumer-oriented omnichannel strategy, akin to the more traditional American big box retailers. Even though The Home Depot’s sales mix has historically been more balanced than Lowe’s’, that might change as revenues from its portfolio of specialty distributors become more significant; The Home Depot is increasingly no longer a single brand but a collection of them (namely: The Home Depot, SRS Distribution, HD Supply, Construction Resources, etc.). Conversely, Lowe’s’ omnichannel and technology investments seem to be paying off for DIYers as well as Pros, with expectations for “Pro growth at 2x the market rate” announced in their latest earnings call, which implies a catching-up to The Home Depot’s historical 50% / 50% DIY / Pro mix and a more balanced, big-box offering that appeals broadly to DIYers and Pros (for less-complex purchase occasions).

Because of the divergence in customer focus, it is difficult to choose one strategy as “better”, but it does seem that The Home Depot’s strategy has been better defined and pursued with greater conviction (as one might expect given the planning and forethought a spate of acquisitions requires). Although it is clear Lowe’s is introducing innovative offerings targeted at greater accessibility, product selection, and price, the ‘Total Home Strategy,’ as it’s referred to at Lowe’s, feels scattershot in that partnerships are leveraged in some instances while more organic in-house development is employed in other instances, creating missed opportunities for greater differentiation and closer customer interaction. In realizing that the best way to connect with its DIY customers is through online- and mobile-first platforms, Lowe’s was prescient, but in partnering with DoorDash to pursue this objective, Lowe’s was myopic.

The e-commerce business model is built on a foundation of data collection and analysis. Leveraging data from online and mobile interactions with customers for the purposes of up-/cross-selling or a more seamless in-person customer experience is what makes e-commerce platforms so compelling for retailers. Additionally, in many retail categories (especially home improvement), the reams of data collected from owned online platforms enable the creation of entirely new offerings or the significant improvement of existing ones. By effectively outsourcing the operation of a significant proportion of e-commerce interactions with DIYers to DoorDash, Lowe’s denies itself many of the business advantages incumbent to the operator of such a platform. Furthermore, it loses substantial control over the rollout of such a new customer experience to an operator with expertise not in home improvement, but in food delivery; as Reddit reviews of the new Lowe’s delivery service via DoorDash reveal, delivering home improvement goods is not exactly the same as delivering food.

Even if partnering does get the offering in front of consumers faster, that may not be beneficial if they are met with a less than satisfactory experience that could derail the “higher conversion rates and lower returns” Lowe’s saw in online sales during the last year. Owning the platform, or at least the customer data fed to it, would enable Lowe’s to customize the delivery process for home improvement-related goods and further optimize many aspects of its business, from inventory to captive finance. The Home Depot, in partnership with point-of-sale solutions provider GreenSky, already offers its customers unsecured home improvement loans as a major piece of its private-label captive finance strategy. In addition to its more traditional credit card offerings, Lowe’s could pursue a similar strategy via a private-label partnership or even independently via a platform developed in-house.

In Home Depot’s case, pursuing the complex Pro is sensible because they are presumably a less elastic, stickier group of purchasers than DIYers and homeowners, which has become important as DIYers slow down on renovations (Figure 5) and new builds continue largely unabated, though moving from a single brand approach to a portfolio of specialty brands could potentially dilute The Home Depot’s brand recognition amongst individual homeowners and consumers. Managing the mix between non-Pro sales coming mainly from The Home Depot stores and Pro sales coming from the specialty distribution brands will become important to maintain attractive margins, as margin compression due to selling low-margin goods to price-comparing Pros at the specialty distributors will almost undoubtedly occur. Sherwin Williams (a leading American paint distributor) (SHW) and the Genuine Parts Company (NAPA Auto parent co., global aftermarket auto parts distributor) (GPC) are interesting comparables for benchmarking The Home Depot’s future prospects as a specialty distributor. Nearly 80% of NAPA/GPC’s revenues are generated from Commercial customers, while about 70% of SHW’s revenues are generated from DIYers and small Pros. Their margin profiles tell an interesting story about specialty distribution firms that are forced to strike a balance between DIYers and Pros: despite both GPC and SHW having 2023 net sales of just over $23 billion, SHW’s profit margin is 10.4%, while GPC’s is 5.7% (Figure 5). The ideal scenario for The Home Depot would be to maintain its historical 50% / 50% DIY / Pro sales mix even as it increases specialty distribution sales, though this will prove difficult given the inorganic acquisition of specialty brands and the already saturated state of sales to DIYers reflected in its balanced sales mix despite The Home Depot’s 2023 sales of more than $152 billion being nearly double Lowe’s’ of $86 billion.

Be sure to subscribe here and connect with me on LinkedIn.

Mentions: LOW 0.00%↑ HD 0.00%↑ SHW 0.00%↑ GPC 0.00%↑