A Protectionist Mountain out of a Steel Molehill:

What the Nippon Steel—U.S. Steel acquisition means for the global steel industry as well as its implications for the 2024 U.S. presidential election and beyond

2006 was an important year for the global steel industry. In China, after “realizing a rough balance [in the trade of steel products] in 2005, [the country became] a net exporter of steel products in 2006,” a status it has retained for nearly two decades thereafter despite a brief Global Financial Crisis-related disruption after 2008 (Figure 1).

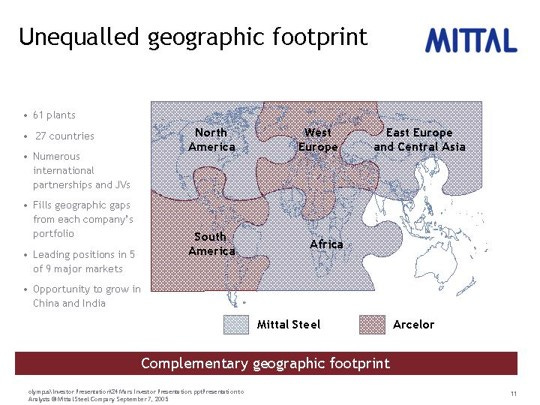

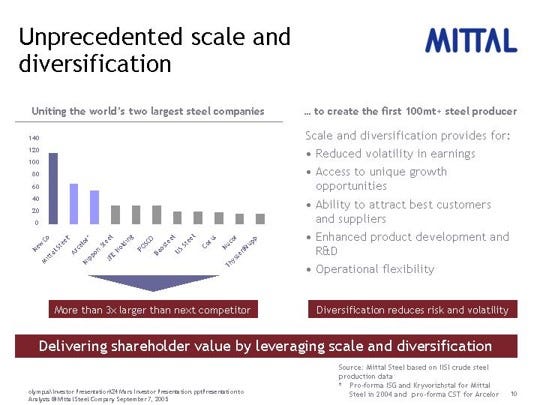

Elsewhere, Indian-owned international steelmaker Mittal was busy pursuing the largest hostile takeover bid the steel industry had ever seen, ultimately offering $34.4 billion for European steelmaker Arcelor, “to create the first [100+ million ton] steel producer,” as Mittal’s transaction rationale slides from the deal claim (Figure 2); in addition to economies of scale in production, Mittal touted the proforma company’s “unrivalled global footprint” as another justification for the deal.

Interestingly, China’s emerging export dominance seems to have been on the minds of executives at the newly-combined ArcelorMittal. In an enumeration of risk factors related to the merger, ArcelorMittal highlights “China [becoming] a net exporter of steel [and its excess steel] exported to [western markets putting] downward pressure on steel prices in those markets in 2006.” Pricing pressure from Chinese firms seems to have been a force pushing the industry towards greater consolidation and globalization, as evinced not only by the ArcelorMittal deal, but by Indian steelmaker Tata’s 2006 acquisition of European steelmaker Corus as well as the “string of deals” Nippon Steel also pursued during the period, including strengthening equity partnerships with steelmakers in Brazil (Usiminas) and Korea (POSCO) in response to a “loss of negotiating power to China, now the world’s biggest buyer of raw materials.”

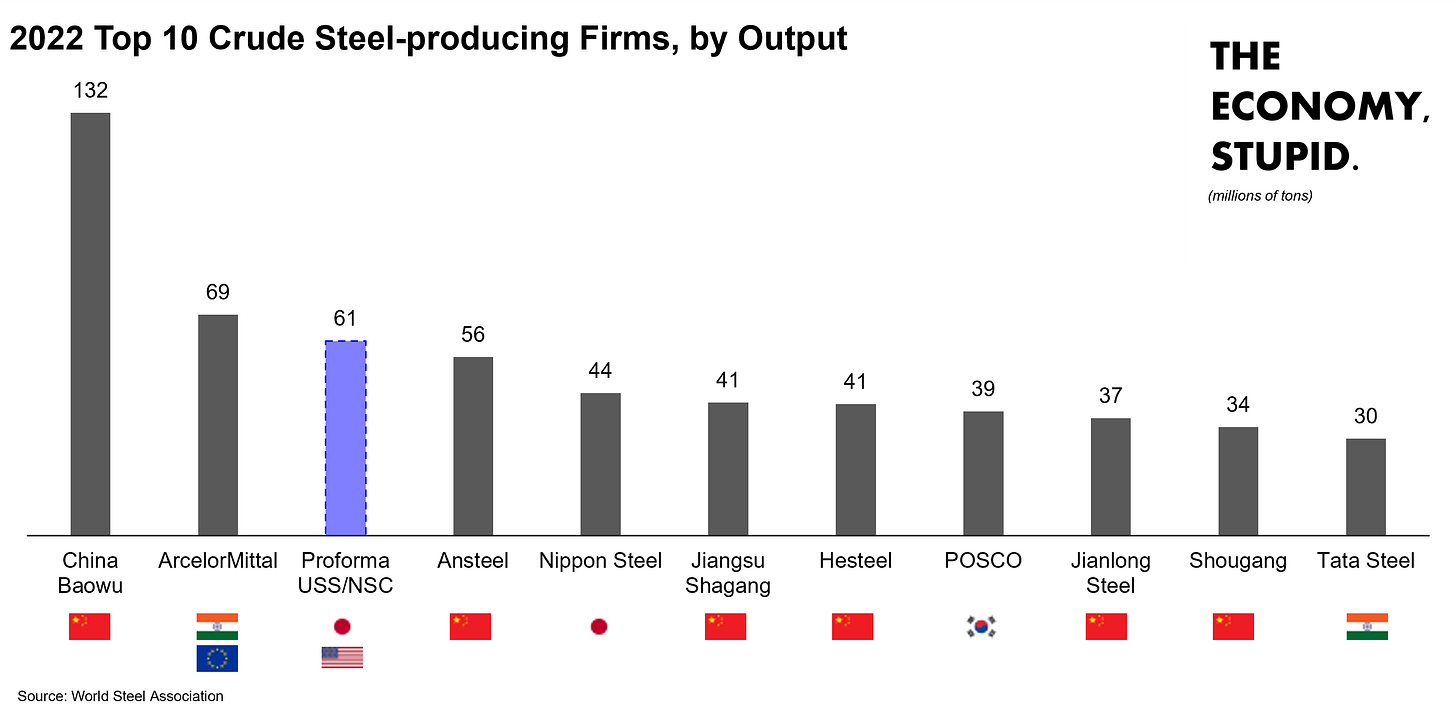

As early as 2006, non-Chinese steelmakers seem to have understood that competition with Chinese steelmakers would fundamentally change the landscape of the industry and necessitate a rethinking of the size and scale of 20th century western steelmakers in America and Europe that had been more competitive in steel production up to that point. A comparison of the top 10 steelmakers in Mittal’s investor presentation from 2006 (Figure 2) with a more recent version from Worldsteel (Figure 3) is striking as it demonstrates how many of the world’s largest steelmakers are now Chinese or non-western, whereas the level of international diversity in the 2006 version of the league table is much higher (the only Chinese steelmaker in the 2006 Mittal league table is Baosteel, a China Baowu predecessor).

Although ArcelorMittal was unable to maintain its proforma 100+ million ton production capacity into the present day, its acquisition strategy seems to have enabled it to withstand much of the competition from new Chinese entrants given it has conceded only one ranking position to a Chinese competitor. Even though Chinese competition has been tougher for the likes of Nippon and POSCO, the only reason both firms still retain top 10 rankings is because of their embrace of strategies similar to ArcelorMittal’s, namely pursuing productive and geographic scale to counter China’s world-beating steelmaking capacity (Figure 4).

Another important difference between the 2006 and 2022 league tables is the complete absence of American firms from the 2022 version. Whereas both Nucor and U.S. Steel were relevant global players in the early 2000s, the industry has undergone a fundamental change in response to Chinese capacity-building that has forced non-Chinese firms to either acquire, be acquired, or stand still and allow Chinese entrants to take market share. ArcelorMittal, Nippon, and others have understood this for years, pursuing acquisitions that have transformed their footprints and operations into global consortia of partnerships (Figure 5) with other steelmakers that also seem to understand the single, fundamental truth in 21st century steelmaking: China is the real competition.

Why, then, if this trend towards globalization and consolidation in the steelmaking industry is decades-old and in response to very clear geoeconomic pressures, has Nippon Steel’s acquisition of U.S. Steel been such a big deal? The issue is largely American politics’ erroneous framing of the issue as well as its infamous myopia.

Given the electoral significance of blue-collar workers in rust belt and swing states, this group of voters has historically been one of particular interest to presidential candidates during campaigns, and the primacy of this constituency is shaping up to be no different in 2024. Donald Trump, the architect of the 2018 steel tariffs that severely disrupted the global industry, is a staunch supporter of protectionist policies meant to satisfy his base of largely blue-collar workers. Biden though, who has been slow to roll back Trump-era tariffs, is embracing protectionism for less ideological motives.

The Biden administration’s stance on the Nippon-U.S. Steel deal seems to be yet another commercial policy concession meant to position the President defensively ahead of what will be an incredibly challenging campaign cycle. To appease key electoral constituencies, it seems the Biden administration is taking a calculated risk in subverting U.S.-Japanese commercial relations (at least temporarily) and enabling Trump-style protectionism for the benefits such a stance may have during campaign events later in the year. The thinking seems to be that the Biden administration cannot realistically support an otherwise mundane transaction since the Trump campaign will almost certainly use any showing of support for the Nippon-U.S. Steel deal against Biden in blue-collar regions that will be key to election success. Taking such a defensive stance may be prudent on what is realistically a minor component of broader commercial and economic issues important to voters, but the Biden administration will need to devise a more offensive strategy in the coming months as defense alone does not win elections.

Instead of defensively playing the waiting game, the Biden administration could use ongoing negotiations between Nippon Steel, U.S. Steel, and the United Steelworkers (USW) union as an opportunity to bolster U.S.-Japanese commercial relations as well as demonstrate to “steel workers [Biden has] their backs,” which is really the administration’s sole goal going into campaign season.

All stakeholders except for USW feel that the terms of the Nippon-U.S. Steel transaction are fair and that the proforma combined company would be in a better place than where the two standalone firms are today. The main issues USW has with the deal are that the “[merging of U.S Steel] into Nippon … will … [create] barriers to enforcing [U.S. Steel’s existing] profit-sharing calculations,” and that “[Nippon Steel] in order to reap the benefit of [its] investment … will take money out of [U.S. Steel] that is needed for investment in [U.S. Steel’s] mills and mines.” Given how a number of steel industry cross-border acquisitions have panned out post-close, these concerns from USW are valid, but they need not hamper a strategically-sound deal meant to bolster western competitiveness in the industry in the face of utter Chinese dominance; the Biden administration (via the Commerce, Labor, and/or Treasury Departments) should be working with USW to 1) incorporate their concerns into the details of the transaction and 2) inform them of the broader geoeconomic implications of the transaction and of the threat Chinese entrants pose not only to U.S. Steel and its USW employees but literally the entire American steelmaking industry. The way forward for American steelworkers is not through protectionism, but through the embrace of partnership with our allies and the forming of western steel ‘consortia’ that can viably compete against China.

In comments at the Asia Society in late 2023, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel stated that “the [U.S.-Japan] relationship … is morphing and transforming from one that was defined by alliance protection to one that’s being defined by alliance projection,” meaning that going forward, America and Japan (together with other allies) need to faithfully present a united front to the rest of the world given increasing multipolarity and alternatives to the American model. He went on to claim that “we keep defining deterrence only by national security,” and that “unlike [the U.S.-Japan] relationship over the last twenty [or] thirty years, we … basically have a mind meld strategically; you don’t have any … salt or sand in the gears [that could be disruptive].” Ambassador Emanuel’s comments feel prescient and timely, but it is up to other stakeholders entrusted with the stewardship of the relationship to ensure his words are heeded.

Mentions: X 0.00%↑

Be sure to subscribe here and connect with me on LinkedIn

Very well written. I’ve heard about the merger but never had a deep dive into it. Thanks for the great article!